Antibiotics and Bacteriophages

by Vanita Dahia

- Antibiotics making you sick?

- Needing more than one course of antibiotics?

- Damaging gut microbiota with antibiotics?

Antibiotics are used extensively throughout one’s life to treat bacterial infections. Antibiotics or antibacterials work on mass killing of detrimental bacteria as well as healthy bacteria which leaves us with a potential to attack by other bugs. Prolonged use of antibiotics allows a great medium for fungi to grow which may manifest as a candida infections. They also wipe out the balance of the good bugs or probiotics.

Probiotics are an emerging and essential part of intestinal health. Probiotics add bacteria to the digestive tract to alleviate intestinal distress and improve immunity. Probiotics have the potential to crowd out harmful bacteria.

Antibiotics should ideally be taken with a probiotic to increase the beneficial bacteria whilst decreasing unfriendly microbes like E. coli.

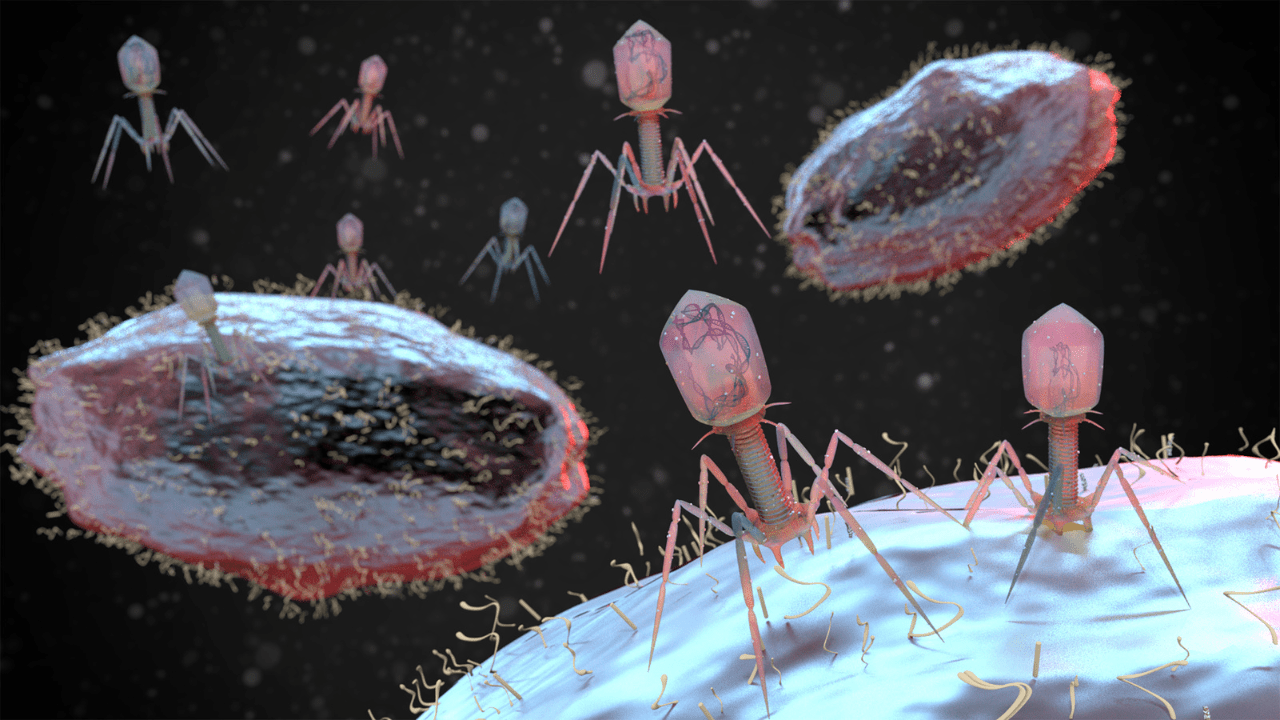

Before antibiotics became available in the 1940s, we used specific nutrients from nature which were capable of attaching itself to the bacterial cell wall and destroying host bacteria. These specific bacteria eating nutrients are called bacteriophages.

Bacteria live in colonies and develop a protective wall around the colony. Bacteriophages have the potential to break down the wall in order for the antibiotics to work effectively.

The targeted use of a bacteriophage is ubiquitous in nature found in soil, animals or the ocean, and can seek out to reduce the infecting organisms that have taken over the intestinal microbiome.

We are just becoming aware of the importance of maintaining the intestinal microbiome, a community of trillions of microorganisms or bugs that live in the gut. We are made up of more bacteria than cells in our body. We become exposed to microbial infestation through consumption of food such as meats, processed carbohydrates, preservatives, additives. Stress and environmental pollutants can also upset the delicate balance of the microbiome which eventually manifests as dysbiosis of the gut.

Dysbiosis is an imbalance of the intestinal microbiota which steadily gets worse as we age, or become stressed, leading to a feeling of “foggy head” or “sick in the stomach”.

Dysbiosis is associated with almost every known disease in mankind from depression, obesity, cancer to cardiovascular disease, diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease.

What you need to know

Many people live in a state of dysbiosis or imbalance that leads to a sense of fogginess, stomach distress or sleep disturbances. Fortunately, shifting the microbiota towards a healthy profile that maintains symbiotic homoeostasis can change the symptoms and development of disease. One important way of improving intestinal microbiota is the use of probiotic bacteria.

Target the harmful bacteria with a bacteriophage whilst replenishing with probiotics to restore the microbiota. Bacteriophage’s can be used independently of an antibiotic.

Antibiotics may be needed for severe microbial infestations.

Phage therapy

Phage therapy is a fascinating approach to fighting bacterial infections that utilizes viruses, specifically bacteriophages (or phages for short).

Phage therapy has been used for a wide variety of infections of the gastrointestinal tract, head and neck, bone, chest; in pathogenic infections such as Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, E. coli, Salmonella, and Pseudomonas. Bacteriophages have been shown in studies to be 80 to 95% successful against pathogenic infestations.

Phages are viruses that naturally target and kill bacteria. They’re incredibly abundant in nature, existing in soil, water, and even our guts.

Phage therapy leverages these natural predators to treat bacterial infections. By introducing specific phages that target the problematic bacteria, the phages can infect and eliminate them.

If you are solitary bacterium, where would you find a friendly or hostile host?

These bugs grow in a colony and inhabit the walled villages interacting with each other. The walled villages produce biofilm which further potentiate infections. Biofilms are commonly found in cystic fibrosis where there is an impaired mucosal delivery clearance, which ultimately predisposes them to loss of respiratory reserve and pneumonia.

- So do we keep adding antibiotics?

- Do we allow the biofilm to persist and propagate itself?

- Familiar with the slime in the mouth upon rising?

Slime is the best way of describing a biofilm. Biofilms develop when you have a foreign body implanted. Examples of foreign bodies are an indwelling catheters or a gastronomy tube, even a piece of shrapnel or lead from a shot gun. Other examples of commonly found biofilms are dental implants, hip or knee prostheses where your own body rejects the implant. A classical biofilm is Methicillin Resistant Staphlococcus (MRSA) infection commonly found in hospital settings.

Researchers have demonstrated that people with fewer bacterial species in the intestine are more likely to develop complications such as cardiovascular disease or diabetes.

Types of Bacteriophages

Nattokinase is once such bacteriophage derived from NATO, a Japanese food made from fermented soybeans. Nattokinase has been shown to dissolve abnormal blood clots and act as a bacteriophage.

Lumbrokinase is a safer bacteriophage derived from the digestive tract of a specific species of earthworms. Lumbrokinase is more potent than Nattokinase which does not interfere with the clotting cascade.

A highly treasured Natural Medicine for Infections

A commonly found herb called Artemisia may be considered as the most powerful complete complex plant defence compound or bacteriophage found in nature. Artemisia comes from the daisy family, also known as wormwood or mugwort and possesses powerful anti-bacterial, antioxidant, anti-parasitic and anti-viral properties.

Food as bacteriophages

Ancient cultures have used vegetables with “slime” content which may play a role in enhancing the microbiome. Foods like drum sticks, lady fingers, also known as okra and natto beans ( Japanese bean) as a few examples of bacteriophages. Increase foods that boost microbiome and gut mucosa.

Testing for Infections and the Microbiome

Managing the microbiota involves assessing the good and bad bugs. The good bugs called probiotics and the bad bugs may be bacterial, fungal or parasitic. Infections can be measured easily in a DIY stool sample by a testing for microbiome mapping.

References

Abedon ST et al, Phage treatment of human infections. Bacteriophage. 2011:1(2):66-85)